Ugly Should Be Allowed [14]

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

Most of the individual buildings in Tokyo are ugly. They are utilitarian, designed to house people affordably, survive earthquakes, and protect inhabitants from the weather. Most could be described as brutalist with concrete or tile exteriors, relatively small windows, and minimal decoration. They aren’t precious or beautiful yet they do what buildings are supposed to do. They function and make Tokyo a surprisingly affordable city for millions of residents and businesses.

Meanwhile, the overall built environment of Tokyo is wonderful. When taken together, the small lots, narrow streets, and intimate shops make the experience of walking the city enjoyable and safe. The density of housing supports a diversity of small businesses. The public transit system is second to none with clean trains that run frequently and are always on time. The city is decentralized with walkable neighborhoods and commercial areas close to housing, parks, schools, and other amenities. It is a perfect example of a 15 minute city - where almost everything you need can be found within 15 minutes of where you live.

The city as a whole is beautiful. The individual buildings take a back seat to the beauty of the urban fabric. The architecture frames the public spaces rather than fight for attention. The infrastructure makes it easy to navigate the city affordably for all residents. The decentralized planning means each neighborhood is walkable and human scaled and fun to explore.

Meanwhile, in America we have taken the opposite approach.

We spend so much time and effort regulating the look, feel, and size of individual buildings we neglect to consider the impact these regulations have on the city at large. Zoning separates uses leading to monotonous districts and reliance on driving to get the basics needed to live. Codes, regulations, layers of review boards and community driven barriers to development aim to control the size, style, and use of what we build. Individually our buildings are thus aesthetically controlled to meet the taste of the lowest common denominator - often older affluent homeowners. The effect: new buildings for the most part are palatable and inoffensive. Yet this comes at a steep cost.

While we argue about style and fight over height limits and density, we are driving up the cost of housing to the point where most people can’t afford to live in desirable neighborhoods or cities. San Francisco, Seattle, New York, and Portland for example, have housing costs that are spiraling out of control, mostly due to laws than enable individuals to throw wrenches in the gears of new developments. The regulations make building new housing risky, expensive, and in some cases almost impossible. Rather than have a set of rules that are predictable and guide developers on what can and cannot be built, these cities have subjective processes that let almost anyone halt a project. Rather than think about the long term benefits a project could have on the entire city, as Brandon Donnelly clearly put it, “for better or for worse, we plan to piss off the least amount of people.”

We have onerous design review processes that add unnecessary risk through increased time and cost to developing new housing, cost that is ultimately passed on to families through higher rental prices, making housing less affordable. Worse, in many cases it prevents new housing from being built at all, as the cost of development outpaces the rents people can afford to pay.

Another result of our approach to urban development is that the lengthy and onerous approval process limits who can develop. It makes it hard for smaller scale projects and incremental development. Instead, we get large development companies building large scaled projects. This doesn’t lead to human scaled cities and thus it reinforces people’s arguments that more codes, regulations, and review boards are necessary. I feel this is a chicken or egg situation. Making it harder to develop leads to only a few large companies able to take on the risk, the more expensive it is leads to larger scale projects to make the numbers work, the larger scale projects make locals concerned of scale and neighborhood character, they pass laws adding design review processes and zoning limitations, which leads to increased development costs. One leads to the other in a vicious cycle.

Rather than building to meet demand, we have a bunch of rules and regulations that limit what can be built where, overriding market forces with individual’s opinions. This creates development patterns that are sprawling and scaled for cars rather than people. It means that much of our urban land is exclusively reserved for single family detached housing, which makes absolutely no sense. Rather than building density in the desirable neighborhoods and city centers, wealthy residents pass laws and take over review boards in order to limit what can be built, preserving low-density neighborhoods at the expense of future residents.

Cities should take a deep honest look at whether their zoning codes, the design review process, and local control is actually benefiting the majority of their residents. Are these things needed at all in order to deliver safe and affordable places to live or open new businesses? I would argue no.

The design review processes coupled with allowing individuals to fight developments on aesthetic grounds is counterproductive, directly increases the cost of housing, and often leads to worse outcomes for our built environment.

Ugly shouldn’t be outlawed. Style shouldn’t be regulated. Individuals should not be able to dictate new developments. Instead, we should open the flood gates and make developing new buildings easier by right. Write a form based zoning code with community input, and then eliminate subsequent review processes that are purely subjective.

Things To Read This Week

There’s Another Way to Pay for Infrastructure Projects

An idea to harvest data from our infrastructure and use sell this new asset to finance new infrastructure projects. The goal, rely less on increasing taxes to build the infrastructure we need and use the data collected from “smart infrastructure” to both improve our systems and fund their upgrades.just like data from smartphone apps create value, the data from physical infrastructure will lead to a new marketplace in which public infrastructure is a lot more attractive to private capital than it is right now.

“Good Design” Is Making Bad Cities, But It Doesn’t Have To

Mostly a critique of unnecessary zoning and design review, they argue that there should be an easier/faster path to building new housing. Delaying, halting, and fighting new development in the name of “neighborhood character” is driving up the cost of housing while preserving inequity in our built environment.In all likelihood, voters, politicians, and courts are going to cling to the idea that aesthetics are fair grounds to contest what happens on a neighbor’s property. But in a time of extreme housing scarcity and out-of-control rents, is a great-looking building still a luxury we have time to wait for?

Mónica Ponce de León on the Future of Architectural Licensure

An interesting take on Architectural Licensure and how it limits diversity. Reform of architecture licensure is needed if we truly care about the profession being more inclusive and diverse. Are architects ready to make big changes?Yes, Other Countries Do Housing Better, Case 1: Japan

I love Japan for so many reasons. The food. The people. The landscape. The culture of craft. Yet I also admire it for how it prioritizes housing abundance and affordability over local obstructionism. Lessons I hope can be adopted in America to combat our housing affordability crisis in cities across the country.Housing obstructionism is a potent impulse among neighbors in Japan, just as it is in other places. It’s a constant in human affairs. But the nation’s centralization of control over buildings makes it moot. The national interest lies in developing compact, walkable, low-carbon neighborhoods with plenty of homes for everyone, and that’s what policy allows, obstructionists be damned…

…The results—in housing abundance, low prices, and walkable, transit-centered, low-carbon urban forms—are remarkable.

Design Inspiration

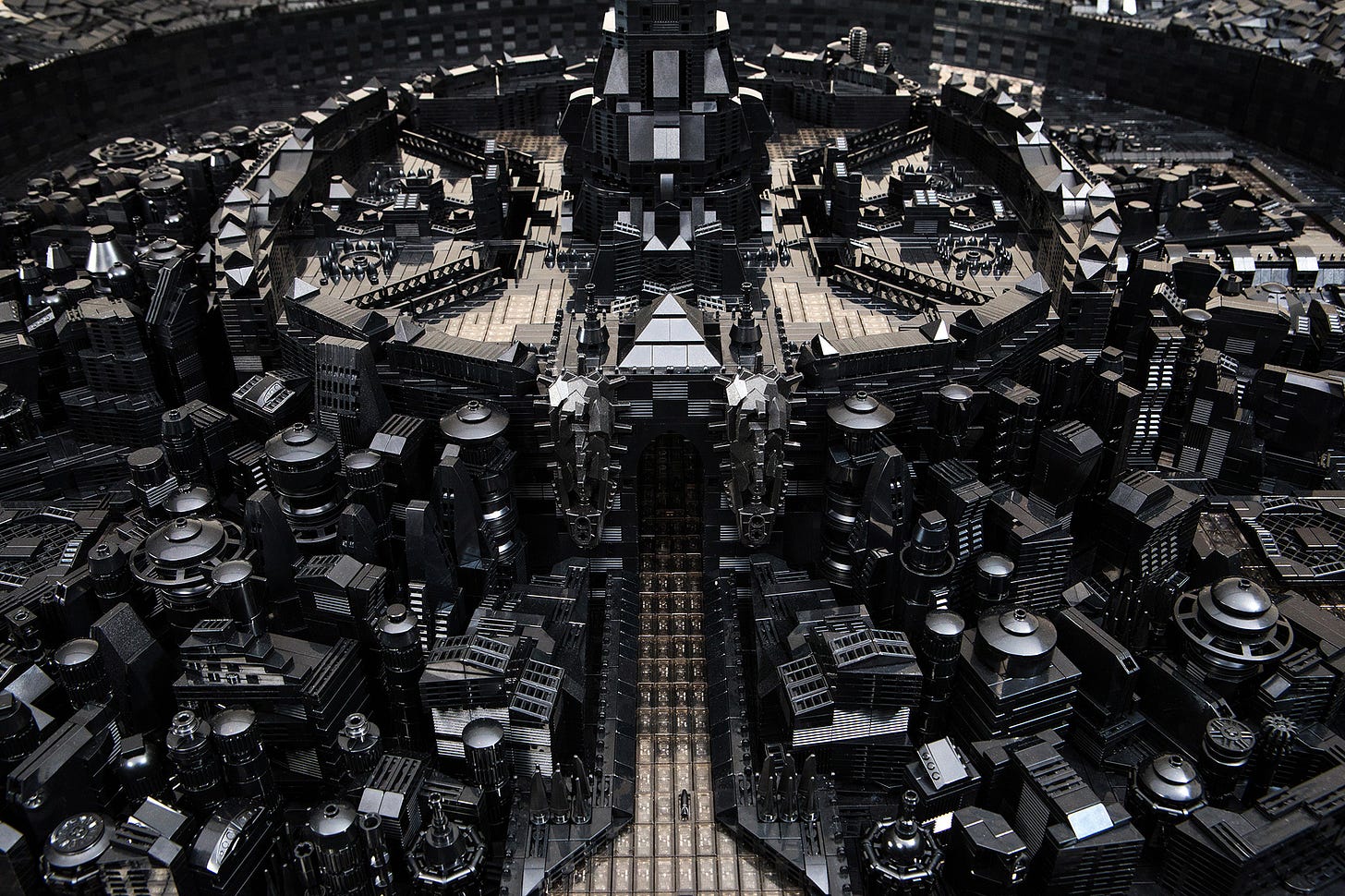

As someone who grew up designing and building with Lego, the artwork of Ekow Nimako resonates with me, both his imaginative world building as well as his fantastical creatures, heroes, and mythology.

Building Black: Civilizations

Inspired by the Medieval Kingdoms of West Africa and the Visionary Scope of Afrofuturism.

Sharing the love

I’ve been a member of the EntreArchitect community for around 10 years now, perhaps longer. It has been a great source of information, comradery, and community as I embarked on my architecture career, started my first architecture firm, and currently as I transition to writing about practice and working as a consultant that helps architects run better businesses. Through the active facebook group and website, there is a collection of resources, documents, podcasts, webinars, and colleagues providing information, advice, and education to help architects focus on the business side of their practice. It has been a valuable resource for me and I recommend checking it out.

Mark LePage started EntreArchitect because he noticed there was a gap in knowledge that many small firms faced. Most architects are not trained in business and the AIA wasn’t focused on the conversations small firm architects wanted or needed to have.

The vision of EntreArchitect™ is to be a great and enduring company by building and maintaining a growing and vibrant community of engaged small firm architects who are seeking success in business, leadership and life.

If you are running a small architecture studio, are thinking about starting your own design business, or work for a small architecture firm, I encourage you to check out EntreArchitect and join the community. Below are some links for where to get started.

Shop for business resources:

Join the EntreArchitect Academy:

Listen to the EntreArchitect Podcast:

Also of note, I’ve recently started managing and editing the EntreArchitect Blog. I help find architects who are interested in writing about issues they face, challenges of practice, or share their expertise with the architecture community. If you are interested in contributing to the blog, please let me know.

Other things I work on:

I recently joined Charrette Venture Group (CVG), where I work with AEC firms across the country to help them run better businesses. We assist with everything from operations and management, financial analysis and strategic planning, to marketing and business development, branding and web design, ownership transitions, and more.

Design and Art: https://www.lucasgraydesign.com/

ADU Plans for sale: https://lucasgraydesign.com/adu-plans

Photography: https://www.instagram.com/talkitect/

Design and Drawings Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/lucasgraydesign/

Email address: lucas@charrettevg.com

Something I Designed